Natures Nation American Art and Environment Peabody Essex Museum Salem Ma

Nature's Nation: American Art and Environs

Curated by: Karl Kusserow and Alan Braddock (organizing curators); Austen Barron Bailly and Karen Kramer (coordinating curators at Peabody Essex Museum)

Exhibition schedule: Princeton University Art Museum, October 13, 2018–January 6, 2019; Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, February 2– May v, 2019; and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, May 25–September nine, 2019

Exhibition catalogue: Karl Kusserow and Alan C. Braddock, Nature's Nation: American Art and Environment, exh. true cat. Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2018. 448 pp.; 326 color and b/w illus. Hardcover $65.00 (ISBN: 9780300237009)

Revisiting Relationships at the Princeton University Art Museum and the Peabody Essex Museum

Fig. 1. Postcommodity, Repellent Argue/ Valla Repelente, 2015. Installation view at US/Mexico Edge, Douglas, Arizona/Agua Pieta, Sonora, 2015. © Postcommodity. Photography past Michael Lundgren; courtesy of Postcommodity and Bockley Gallery

Visitors who come to the exhibition Nature'south Nation: American Art and Environment at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) with the expectation of seeing soothing paintings of landscapes may be initially startled past a looming object at its archway: a conspicuous yellow balloon emblazoned with a stark, staring scare eye, commonly used to affright farm and garden pests. As office of an installation staged past the arts collective Postcommodity in 2015, entitled Repellent Debate/Valla Repelente (fig. 1), this was ane of an array of xx-six similar airborne balloons that rose one hundred feet above a 2-mile long perpendicular line crossing the United states-Mexico border. The temporary land-fine art monument was besides a community appointment project that sparked dialogue about geopolitical systems, permeable national boundaries, and the surveillance apparatus of the modern nation-state. Withal the motif of the spiritually powerful all-seeing heart, common to many Indigenous cultures, as well acts equally a reminder that arbitrary demarcations cannot contain the power of shared ideas, peculiarly ones arising with urgency in the midst of a transnational environmental crisis.

The Postcommodity project invited beholders to adopt a changed perspective and to see the globe anew; so does Nature'south Nation: American Fine art and Environs. Leading off with the multilayered, disquisitional, and interdisciplinary piece of work of Postcommodity sets an important tone: it affirms a curatorial framework that responds to our present, perilous planetary circumstances. All of the objects on view at the PEM presentation piece of work together to reframe a history of American art and environmentalism. Plenty of paintings will satisfy the want of visitors to encounter canonical American landscapes—works by Thomas Cole, Asher Durand, Thomas Moran, and Frederic Edwin Church building that historic natural wonders—just throughout, the traditional ethics they exemplify are subject to revisionist reevaluation. Presenting such historical landscapes alongside contemporary fine art, and in dialogue with work past both historical and contemporary Native American artists, the bear witness weaves a story nigh the circuitous, conflicted dialectic of nation-building and reflects upon its repercussions in a time of pivotal climactic change.

Fig. 2. Nature's Nation installation view. Salem, MA. Courtesy Peabody Essex Museum; photography past Ken Sawyer

Nature's Nation is organized by the Princeton Academy Art Museum, and the exhibition and accompanying catalogue borrow the title from Perry Miller'south 1967 written report of American literature, placing comingled ideas about nature and selfhood in the United States nether new scrutiny.1 Information technology was cocurated by Karl Kusserow, John Wilmerding Curator of American Art, and Alan C. Braddock, Associate Professor of Art History and American Studies at the College of William & Mary. At the PEM, curators Austen Barron Bailly and Karen Kramer spearheaded a modest revision of the bear witness, with the valuable addition of more a dozen works from the Salem museum'southward collection of Native American art. Altogether, well over 100 works are on view, spanning 300 years of creative enterprise, past artists such every bit Charles Willson Peale, John James Audubon, Asher Durand, Robert Due south. Duncanson, Georgia O'Keeffe, Aaron Douglas, Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, Ana Mendieta, Robert Smithson, Mateo Romero, Alan Michelson, Alexis Rockman, and Theaster Gates, to proper noun only a few (fig. 2). The arrangement of paintings, illustrations, sculpture, decorative arts, and inter-medial installations explores how artists, as well as scientists and activists, have regarded the ecologies within which we alive aslope other entities: organic and inorganic, fellow humans and nonhuman animals alike.

The fourth dimension is ripe, even overdue, for art museums to engage with climate science, just every bit many contemporary artists accept been doing for decades.2 On March 15, 2019, young activists mounted a global protest of inadequate governmental and corporate response to impending climate ending, dramatizing the terrifying and bluntly pessimistic warnings that have rung out every few weeks over the past several years. In May, the 500 scientists comprising the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) released a report detailing rapidly expanding regions of uninhabitability; in their survey, devastating testify far exceeds any adept news. Withal, the timeliness of this exhibition and the stand information technology takes bring attention to the environmental interrelationships that fine art shares with all other human occupations: it draws attention to its historical complicity, its internal contradictions, and also, more than optimistically, its chapters to intervene in a planetary crunch which may seem too overwhelming to comprehend.

Nature's Nation invites an interactive visiting experience, addressing school-historic period visitors and families as well as viewers more familiar with the conventional narratives of American art. At its entrance, and throughout its galleries, prominent questions affirm the prevailing concern of the curators: "What are the environmental implications of a work of art?" The works assembled in the first half of the exhibition infinite show how art shaped public understanding of humanity'southward place within the natural world. Images have sanctioned behaviors, affirmed beliefs, or confirmed biases that took hold in the early colonial period and coalesced in the nineteenth century. Whether intentionally or otherwise, artists reflected the imperialist premises of American exceptionalism. When the United States took possession of North American land and resources, its reifying attitudes toward nature supplanted Indigenous practices of abode and reciprocation. Therefore, the exhibition revisits the centrality of landscape in American art, not only as a pictorial genre but as well in terms of the conceptual terrain on which the nation forged its self-identity. Equally scholars such every bit William Cronon have demonstrated, cherished representations of pristine wilderness staked an aesthetic merits to the land and showed beholders how to think about nature every bit a treasure to which only some were granted entitled access, while other people and animals were contained, managed, or forcibly removed.three

Fig. 3. Thomas Cole (1801–1848), A View of the Mount Pass Called the Notch of the White Mountains (Crawford Notch), 1839. Oil on canvas, xl i/8 x 61 1/iv in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew West. Mellon Fund

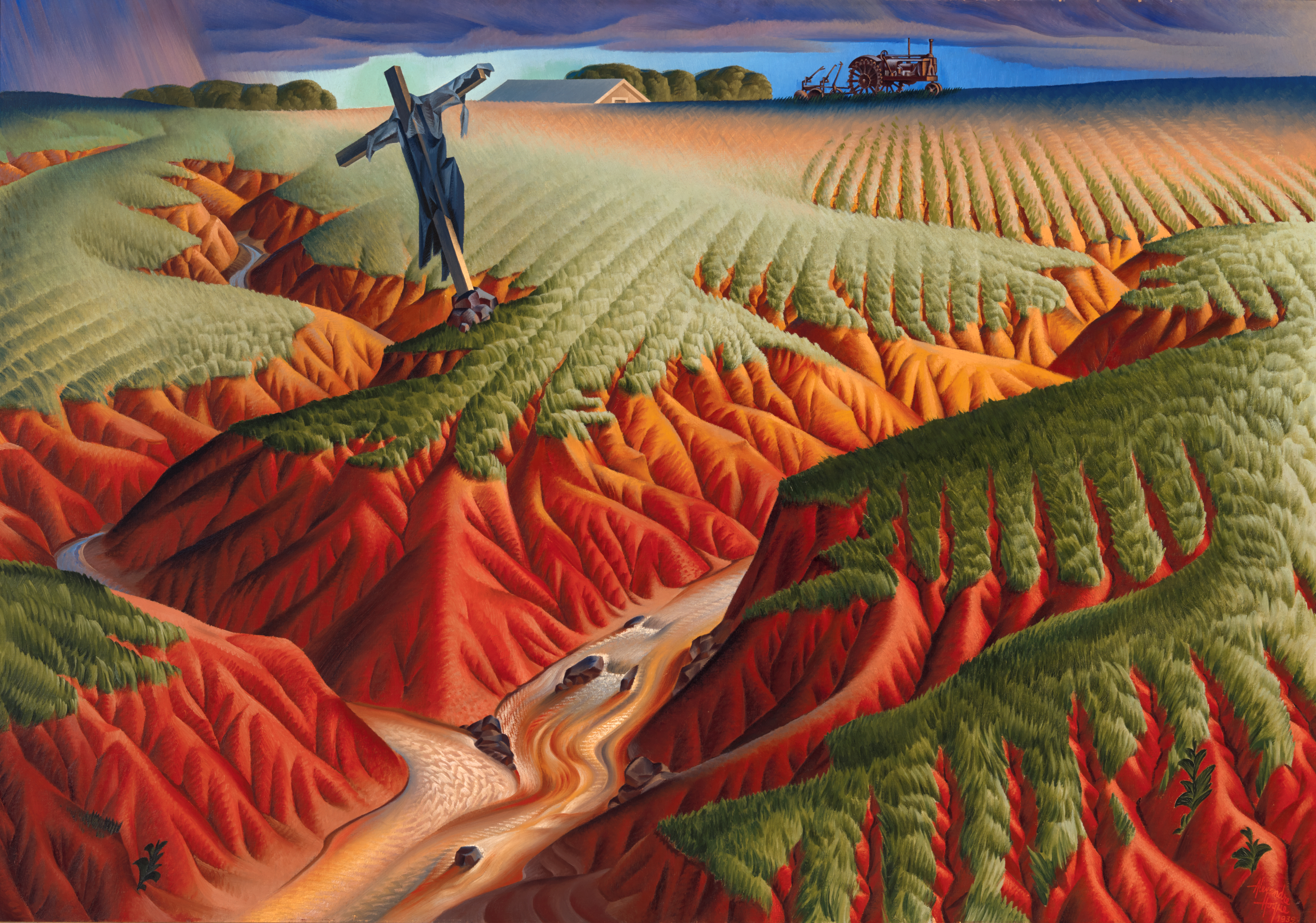

In place of standard summaries or soothing myths, the exhibition solicits active engagement between beholders and works of art and provokes recognition of the oft troublesome attitudes to which they grant visual class. Some of these works openly celebrate profligate natural exploitation, such as James Hamilton'southward eerie Called-for Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania (c. 1861; Smithsonian American Art Museum); others, such as Thomas Cole's 1839 A View of the Mountain Pass Called the Notch of the White Mountains (Crawford Notch) (fig. 3), are more ambivalently assimilationist, treating wilderness as a resource as worthy of respect and utilization. Still others are uncompromisingly critical: in the second half of the exhibition, mod and contemporary artists show a more self-consciously environmentalist perspective that emerged slowly in the mid-twentieth century, peculiarly after the groundbreaking and revelatory 1962 book Silent Spring by Rachel Carson.four The condemnation of destructive farming in Crucified Land (1939) by Alexandre Hogue (fig. four) matches the grim reproach of the photograph CF00068 (2009) past Christopher Jordan from the series Midway: Message from the Coil, showing a expressionless albatross, its decomposable carcass revealing a pile of ingested plastic debris.

Alexandre Hogue (American, 1898-1994). Crucified State, 1939. Oil on canvas, framed: 47 one/viii × 65 1/2 × ii 1/16 in. (119.7 × 166.4 × v.two cm). GM 0127.2000. Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The didactic texts in the PEM galleries echo the exhibition catalogue in stressing dynamic interchange amid what Donna Haraway has termed natureculture.v Small tables and chairs in the galleries offer relevant books for visitors to peruse and discuss, such as Carson'due south Silent Bound, alongside the exhibition catalogue. This publication expands well across the limits of the exhibition, serving as a long-awaited follow-upwards to Alan Braddock and Christoph Irmscher's 2009 anthology of ecocritical essays, A Keener Perception.6 Beyond the valuable summary essays information technology includes by Kusserow and Braddock, it also features topical contributions by scholars in a variety of fields, including Rachael Z. DeLue, Robin Kelsey, Miranda Berlarde-Lewis, Laura Turner Igoe, Kimia Shahi, Jeffrey Richmond-Moll, and Anne McClintock, equally well equally essays by artists Marker Dion and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and environmental theorists Timothy Morton and Rob Nixon, amongst others.

Fig. five. Tlingit Naaxein (Chilkat Robe), before 1832. Mountain goat wool and cedar bark, 53 ten 63 3/4 in. Peabody Essex Museum; Souvenir of Captain Robert Bennet Forbes, 1832 © 2010 Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Walter Argent

The versions of the exhibition at Princeton and Salem share a common mission, although their emphasis and organization differ. In the former, the first room assembled diverse objects in a "cabinet of curiosities," highlighting ecocritical connections among materials, across widely differing mediums, and, most importantly, between cultures and species. At the doorway, such dynamic interchange was established by the organization of a Tlingit Naaxein (Chilkat Robe), made in the early on nineteenth century of mount caprine animal wool, cedar bark, and leather (fig. v), next to a photograph past Subhankar Bannerjee, Caribou Migration I (Oil and the Caribou, Coleen River Valley) (2002; Collection Lannan Foundation), tracking annual migration patterns in the threatened Chill National Wildlife Refuge. Both faced Thomas Moran's grandiose tribute to American wilderness, Lower Falls, Yellowstone Park (1893; Gilcrease Museum), an apotheosis of the period commemoration of seemingly unoccupied nature. Nearby, contemporary creative person Valerie Hegarty's Fallen Bierstadt (2007; fig. vi) hung side by side to the original painting that inspired it, Albert Bierstadt'due south Bridal Veil Falls, Yosemite (c. 1871–73; North Carolina Museum of Art), showing dialogue between a cherished nineteenth-century painter and his twenty-first-century interlocutor; the pairing was all the more poignant in light of the recent devastating California wildfires. On an adjacent wall, the modernity of Morris Louis'southward painting Intrigue (1954; Princeton University Art Museum) contrasted with the ornate elegance of a eighteenth-century mahogany highboy, an anarchistic comparison that illustrated how the materials of both fine and decorative arts are bound up in global networks of unsustainable mining, logging, and agriculture; in forced labor; and in toxic pollution. One of the great pleasures of the exhibition came in seeing familiar works have on new, reinvigorated relevance in such comparative arrangements.

Fig. half-dozen. Valerie Hegarty (b. 1967), Fallen Bierstadt, 2007. Foamcore, paint, paper, glue, gel medium, sheet, wire, and wood, 70 x l x sixteen 3/iv in. Brooklyn Museum, Souvenir of Campari, USA 2008 © Valerie Hegarty

In place of Princeton's eclectic introductory gallery, the PEM installation opens by contrasting Native American symbiotic human and natural relations with the extractive logics of Eurocentric worldviews. Indigenous art forms that illustrate a cosmological and material connection to place, such as the Tlingit robe and a video installation of traditional and contemporary Tlingit dancing by Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/Unganax), are displayed adjacent to Euro-American books, paintings, and scientific illustrations reflecting Enlightenment-era taxonomic systems. The works of contemporary artists Walton Ford and Mark Dion hang near the historical objects that inspired them, offering comment on the nineteenth-century preoccupations with collecting and categorizing that underwrote the colonizing mission of the nation. As Galanin's thrumming soundtrack echoes beyond the exhibition spaces, these very different means of thinking and knowing demonstrate tragic cultural and environmental consequences, lingering in retentiveness as viewers next come across familiar vistas of nature's sublime grandeur.

Iii broad, roughly chronological sections provide the thematic construction of the exhibition, but these seep into and traverse 1 another every bit well: The Order of Things examines models of ecological interconnectivity alongside humanistic hierarchies; Visualizing Man Impacts summarizes attitudes toward aestheticized utilitarian nature; and Vital Forms encompasses responses to more acutely realized environmental threats. Subsections devoted to New Views and Ethics emphasize ecological inter-permeation, although some of the categories reflect equally much compartmentalization as interchange. While a department devoted to Cities is a useful reminder that urban spaces are also environments, the separate sections devoted to Portraits, Landscape, Cities, and Animals role in some contradiction to the spirit of ecocriticism. The mahogany highboy is similarly sequestered in its own niche, although information technology partners with other sections devoted to substances and extractive processes, such equally sugar, silver, and turpentine, which shed important light on exploitative human and cloth entanglements alongside artful design.

The exhibition offers equal opportunity for retrospective regret and hope. Almost of the contemporary work appears in the terminal galleries, demonstrating alternately dire, analytical, and wryly optimistic visions of America's history and future. The Browning of America (2000; Crocker Art Museum) by Jaune Quick-to-Run across Smith (Salish member, Confederated Salish-Kootenai nation) is a mixed-media assemblage of newspaper clippings upon which a map of the contiguous United States has been traced, topped past painted pictograms of human being and animal forms. As leaky drips of boundary-defying fluid rise counterintuitively upward across the surface, the map seemingly cannot contain either the seeping brown matter or the Ethnic presence to which information technology corresponds. Yet, if the prototype reflects upon the inexorable spread of pollution, or laments lost Native American communities, it also draws upon current census forecasts to propose a decolonized hereafter in which the browning of the American population unseats its presumptive white majority.

Correspondingly complex, transnational forces emerge in the visually striking photographs of Bannerjee, Hashemite kingdom of jordan, and Canadian artist Edward Burtynsky. If these works aestheticize the crisis, other more than activist projects provide an of import complement: the mirror shields fabricated for the 2016 customs performance and video piece by Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara/Lakota). which engaged with the Continuing Stone pipeline protestation, remind visitors that responding to ecological crisis involves more than consciousness raising and pictorial gestures.

Nature's Nation is not art-historical business as usual, and it may strike some as reductive in its strong and indeed politicized point of view. To me, this is a welcome alter: the straight and purposeful simplification of a long, complicated, and often contradictory story serves a greater purpose. The exhibition delivers an imperative message—artists and museums must find ways to appoint viewers and to foster a sense of collective stewardship in which promotion of ecologically sound ways of life will complement social, racial, and environmental justice. At the cease, equally visitors listen to the audio track of dancing water protectors in Luger'south protestation action, they are offered cards and wall space on which to articulate their biggest concerns or voice their commitments. Past providing a forum for both personal and commonage activeness to take shape, the presentation leaves viewers with a sense of promise amid calamity.

Cite this commodity: Emily Gephart, "Revisiting Relationships at The Princeton Academy Art Museum and the Peabody Essex Museum," review of Nature's Nation: American Art and Environment, Princeton University Art Museum and Peabody Essex Museum, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Leap 2019), https://doi.org/x.24926/24716839.1709.

PDF:Gephart, review of Nature's Nation

Notes

About the Writer(due south): Emily Gephart is a Lecturer in Visual and Critical Studies at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University

Source: https://editions.lib.umn.edu/panorama/article/natures-nation/

0 Response to "Natures Nation American Art and Environment Peabody Essex Museum Salem Ma"

Post a Comment